Exposure to common cold coronaviruses can teach your immune system to recognize COVID-19 using memory T cells, according to a new study that could have huge implications for the search for a vaccine

Last month, we wrote about T-cell immunity after scientists discovered some coronavirus patients recovered from COVID-19 infection, but mysteriously did NOT have any antibodies against the virus. Since then, they have learned a lot more about the other types of T-cell as they relates to the new COVID-19

In a new study that could have huge implications for the search for a vaccine, scientists found that an exposure to common cold coronaviruses can teach your immune system to recognize SARS-CoV-2. The study, which was led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) and published on August 4, 2020 in Science, may explain why some people have milder COVID-19 cases than others—though the researchers emphasize that this is speculation and much more data is needed.

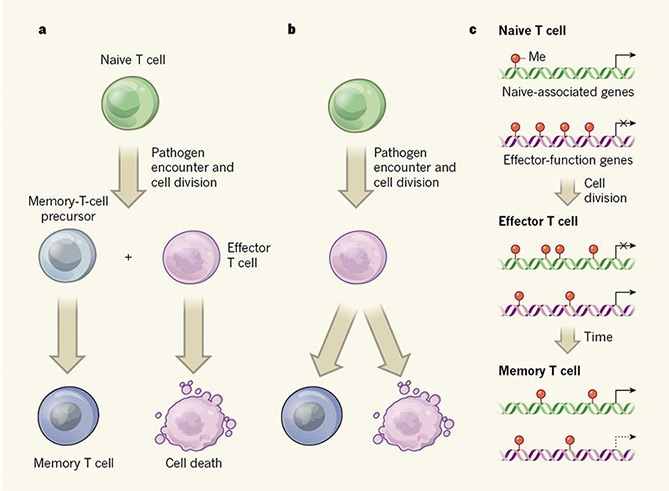

The researchers found that immune system’s “memory” T cells keep track of the viruses they have seen before. This immune cell memory gives your cells a headstart in recognizing and fighting off repeat invaders. With “memory” T cells, people who have recently been infected by certain cold viruses may actually be some of the same people who when infected with SARS-CoV-2 don’t seem to get sick. It’s like they were previously “naturally vaccinated “ against SARS-CoV-2.

However, researchers cautioned that it is too soon to say whether pre-existing immune cell memory affects COVID-19 clinical outcomes. It’s still unclear how memory T cells are generated despite the fact that it is an understudied field. Vaccines have been around since 1776 when Edward Jenner invented the first vaccines as a method to protect against smallpox. Understanding the origins of memory T cells will be beneficial to vaccine design.

LJI Research Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D., who co-led the new study with LJI Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci, said:

“We have now proven that, in some people, pre-existing T cell memory against common cold coronaviruses can cross-recognize SARS-CoV-2, down to exact molecular structures,” says LJI Research Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D., who co-led the new study with LJI Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci. “This could help explain why some people show milder symptoms of disease while others get severely sick.”

“Immune reactivity may translate to different degrees of protection,” adds Sette. “Having a strong T cell response, or a better T cell response may give you the opportunity to mount a much quicker and stronger response.”

As we explained here last month, T-cells are a kind of immune cell (a type of lymphocyte) whose main purpose is to identify and kill invading pathogens or infected cells. They are a part of the immune system that focuses on specific foreign particles. They do this using proteins on its surface, which can bind to proteins on the surface of these imposters.

A T-cell develops in the thymus gland (hence the name) and plays a central role in the immune response. Rather than generically attack any antigens, T-cells circulate until they encounter their specific antigen. As such, T cells play a critical part in immunity to foreign substances.

However, a small portion of long-lived T cells still remains for rapid response upon pathogen re-exposure. This kind of cells is called memory T cells. Memory T cells that circulate in the blood and are present in lymphoid organs are an essential component of long-lived T cell immunity. These memory T cells remain poised to rapidly elaborate effector functions upon re-exposure to pathogens.

Because memory T cells have been trained to recognize specific antigens, they will trigger a faster and stronger immune response after encountering the same antigen. This is how vaccines work to protect us against infection.

The new work builds on a recent Cell paper from the Sette Lab and the lab of LJI Professor Shane Crotty, Ph.D., which showed that 40 to 60 percent of people never exposed to SARS-CoV-2 had T cells that reacted to the virus. Their immune systems recognized fragments of the virus it had never seen before. This finding turned out to be a global phenomenon and was reported in people from the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom and Singapore.

Scientists wondered if these T cells came from people who had previously been exposed to common cold coronaviruses—what Sette calls SARS-CoV-2’s “less dangerous cousins.” If so, was exposure to these cold viruses leading to immune memory against SARS-CoV-2?

For the new study, the researchers relied on a set of samples collected from study participants who had never been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. They defined the exact sites of the virus that are responsible for the cross-reactive T cell response. Their analysis showed that unexposed individuals can produce a range of memory T cells that are equally reactive against SARS-CoV-2 and four types of common cold coronaviruses.

This discovery suggests that fighting off a common cold coronavirus can indeed teach the T cell compartment to recognize some parts of SARS-CoV-2 and provides evidence for the hypothesis that common cold viruses can, in fact, induce cross-reactive T cell memory against SARS-CoV-2.

“We knew there was pre-existing reactivity, and this study provides very strong direct molecular evidence that memory T cells can ‘see’ sequences that are very similar between common cold coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2,” says Sette.

Looking closer, the researchers found that while some cross-reactive T cells targeted the SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein, the region of the virus that recognizes and binds to human cells, pre-existing immune memory was also directed to other SARS-CoV-2 proteins. This finding is relevant, Sette explains, since most vaccine candidates target mostly the spike protein. These findings suggest the hypothesis that inclusion of additional SARS-CoV-2 targets might enhance the potential to take advantage of this cross reactivity and could further enhance vaccine potency.

Below is the abstract of the study.

Abstract

Many unknowns exist about human immune responses to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. SARS-CoV-2 reactive CD4+ T cells have been reported in unexposed individuals, suggesting pre-existing cross-reactive T cell memory in 20-50% of people. However, the source of those T cells has been speculative. Using human blood samples derived before the SARS-CoV-2 virus was discovered in 2019, we mapped 142 T cell epitopes across the SARS-CoV-2 genome to facilitate precise interrogation of the SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4+ T cell repertoire. We demonstrate a range of pre-existing memory CD4+ T cells that are cross-reactive with comparable affinity to SARS-CoV-2 and the common cold coronaviruses HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, or HCoV-HKU1. Thus, variegated T cell memory to coronaviruses that cause the common cold may underlie at least some of the extensive heterogeneity observed in COVID-19 disease.