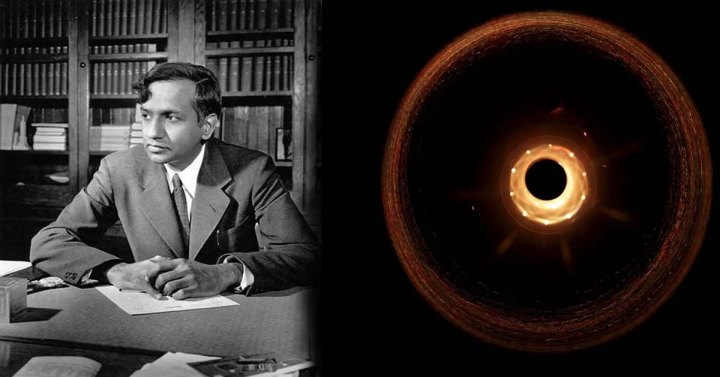

He Drove 150 Miles to Teach Only 2 Students: The Enduring Dedication of Nobel Laureate Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar was a giant in the world of astrophysics, a brilliant mind whose contributions to theoretical physics earned him the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics, shared with William A. Fowler for their groundbreaking work in “…theoretical studies of the physical processes of importance to the structure and evolution of the stars.”

Born in Lahore in 1910, during the era of the British Raj in present-day Pakistan, Chandrasekhar hailed from a Tamil Brahmin family. His early education, guided by his parents, laid the foundation for his remarkable journey. Despite being homeschooled until he was 12, he excelled in mathematics and physics, nurtured by his father and mother alongside his Tamil lessons.

His academic journey led him to Presidency College, Madras (now Chennai), and later to the University of Cambridge. Chandrasekhar eventually settled in the United States, where he spent the majority of his career. He became a distinguished professor at the University of Chicago, serving there for nearly six decades and conducting groundbreaking research at institutions like the Yerkes Observatory. His tenure also included an editorial role at The Astrophysical Journal for almost two decades.

Chandrasekhar’s mathematical approach to studying how stars evolve has greatly influenced our understanding of the later stages of massive stars and black holes. His work has led to the development of numerous theoretical models that are still used today. Additionally, many important ideas, organizations, and even physical objects, like the Chandrasekhar Limit and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, bear his name as a tribute to his contributions.

Chandrasekhar’s Dedication to Teaching

Beyond his scholarly achievements, Chandrasekhar’s commitment to his students stands out. He maintained a close working relationship with them, insisting on being addressed as “Prof. Chandrasekhar” until they earned their PhDs.

Chandrasekhar went the extra mile for his students, quite literally. During his tenure at the Yerkes Observatory in the 1940s, he commuted 150 miles (240 km) every weekend between the Yerkes Observatory and the University of Chicago to teach a class attended by just two students.

When asked why he invested so much in these two students. His reasoning, as he put it, was simple: “They were very good students.” And indeed, they proved to be exceptional. Those two students, Lee Tsung-Dao and Yang Chen-Ning, eventually rose to scientific prominence, earning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957, before he could get one for himself. Their Nobel Prize win underscored Chandrasekhar’s exceptional ability to identify and nurture scientific talent.

In 1983, Chandrasekhar was honored with the Nobel Prize in Physics, recognizing his pioneering work alongside William A. Fowler. Their theoretical studies significantly advanced our understanding of stellar evolution and the structure of stars. The Chandrasekhar limit, a cornerstone concept in astrophysics, is named in his honor, as is the Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

Accounts from his lectures reveal his dedication to intellectual rigor, as frivolous questions were swiftly dismissed, while substantive inquiries received thoughtful consideration. This approach, as recounted by astrophysicist Carl Sagan, reflects Chandrasekhar’s commitment to cultivating excellence in scientific inquiry.

“Frivolous questions” from unprepared students were “dealt with in the manner of a summary execution”, while questions of merit “were given serious attention and response,” Carl Sagan noted.

Chandrasekhar passed away from a heart attack at the University of Chicago Hospital in 1995, having previously experienced one in 1975. He is survived by his wife, who herself had a deep interest in literature and Western classical music. She lived until September 2, 2013, reaching the age of 102. A big shoutout to Andriy Burkov for bringing attention to the story today on X (formerly known as Twitter).