Largest real-world study conducted by Oxford University found that covid vaccines are less effective than advertised

For months, Pfizer and Moderna had advertised their covid vaccines as having efficacy rates of over 90% against Covid-19 after two doses. In a statement on its website, Pfizer said “Analysis of 927 confirmed symptomatic cases of COVID-19 demonstrates BNT162b2 is highly effective with 91.3% vaccine efficacy observed against COVID-19, measured seven days through up to six months after the second dose.”

At one point, Pfizer even said its “vaccine was 100% effective against severe disease.”

“The vaccine was 100% effective against severe disease as defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 95.3% effective against severe COVID-19 as defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Safety data from the Phase 3 study has also been collected from more than 12,000 vaccinated participants who have a follow-up time of at least six months after the second dose”

Less than three weeks ago, a new Pfizer-funded study found that the Pfizer vaccine is still 88% effective at preventing serious illness. But now a new landmark study casts serious doubts on covid vaccines’ claims.

In the largest study of its kind, Oxford University and the UK Office for National Statistics analyzed more than 3 million PCR tests from a random sample of people. The study researchers later examined the efficacy of COVID vaccines in the wild, and unsurprisingly they found that the efficacy rates for the Pfizer and Moderna are significantly lower than the 90%+ rates first advertised from the initial controlled trials.

The study, which was led by Oxford senior researcher and available in preprint version, was published Thursday on the Oxford University website. The authors of the study found that Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines still offer “good” protection against new infections, but their efficacy has been reduced compared with Alpha.

The study also found that while the “two doses of either vaccine still provided at least the same level of protection as having had COVID-19 before through natural infection, those who had been vaccinated after already being infected with COVID-19 had even more protection than vaccinated individuals who had not had COVID-19 before.”

Further corroborating the Oxford study, Simon Clarke, an associate professor in cellular microbiology at the University of Reading said:

“We’re seeing here the real-world data of how two vaccines are performing, rather than clinical trial data, and the data sets all show how the delta variant has blunted the effectiveness of both the Pfizer and AstraZeneca jabs.”

The study also shows the differences between vaccines: for example, the Moderna jab had “similar or greater effectiveness” against the delta variant as a single dose of the other vaccines. And while the Pfizer and Moderna jabs showed greater initial efficacy against infection than the AstraZeneca jab, this protection premium erodes after only 4-5 months.

The study also found that “a single dose of the Moderna vaccine has similar or greater effectiveness against the Delta variant as single doses of the other vaccines.” The study also shows that while “two doses of Pfizer-BioNTech have greater initial effectiveness against new COVID-19 infections, but it declines faster compared with two doses of Oxford-AstraZeneca.”

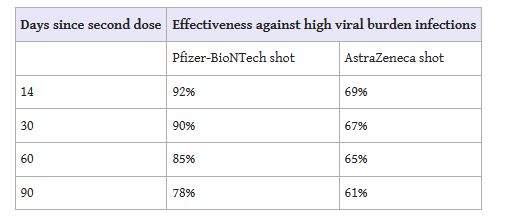

Below is a table showing how the efficacy of vaccines degrades over time. As you can see from the table below, the efficacy of Pfizer’s vaccine drops to 78% in just 90 days contrary to Pfizer’s claims of 84% after 4 to 6 months.

Credit: Bloomberg

Despite all this, even after receiving two doses of a jab, those infected with delta showed much higher peak levels of the virus than those infected with alpha or some other variant. Finally, the study also found that while the Pfizer and Moderna jabs showed greater initial efficacy against infection than the AstraZeneca vaccine, this protection erodes after only after four to five months.

Sarah Walker, a professor of medical statistics and epidemiology at Oxford who helped lead the study, also told Bloomberg that: “The U.K. results cast further doubt on the possibility of achieving herd immunity via vaccination.”