Here is why NFTs are harmful and bad for the environment

No day goes by without another headline about NFTs or non-fungible tokens. The NFT market is exploding and celebrities like Mark Cuban, Beeple, and Lebron James are already cashing in. Just last week, Tesla founder and CEO Elon Musk turned down a $1 million offer to buy his tweet as an NFT. A few days earlier, Christie’s Auction sold Beeple’s NFT for a record-setting $69.3 million, making it the most expensive digital art ever sold.

We’ve been covering NFTs for several weeks now. The crypto-fueled craze is taking the internet by storm. For those of you who’re new to the NFT world, NFT is a type of cryptographic token that lives on a blockchain network that represents a unique digital asset. This asset can either be entirely digital assets or tokenized versions of real-world assets. Because NFTs are not interchangeable with each other, they may function as proof of authenticity and ownership within the digital realm, for example as proof of the authenticity of rare art.

However, behind these frenzies, the dark side of NFT that not many people are talking about is its impacts on the environment. NFTs are bad for the environment as you shall see later in this piece. To really understand how NFTs are created, we first need to understand how blockchain and Ethereum works.

The vast majority of NFT tokens were built using one of two Ethereum token standards (ERC-721 and ERC-1155). The creation and issuance of NFTs are also governed by various standard frameworks. The most prominent one is ERC-721, a standard for the issuance and trading of non-fungible assets on the Ethereum blockchain.

Second, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and most major cryptocurrencies use a consensus algorithm known as Proof-of-Work (PoW). This allows information to be stored in a distributed, decentralized manner across many nodes in a network (e.g. The Internet) while remaining secure, reliable and dispute-free. (There are alternatives to PoW which are far more efficient, but PoW is currently the most widely used).

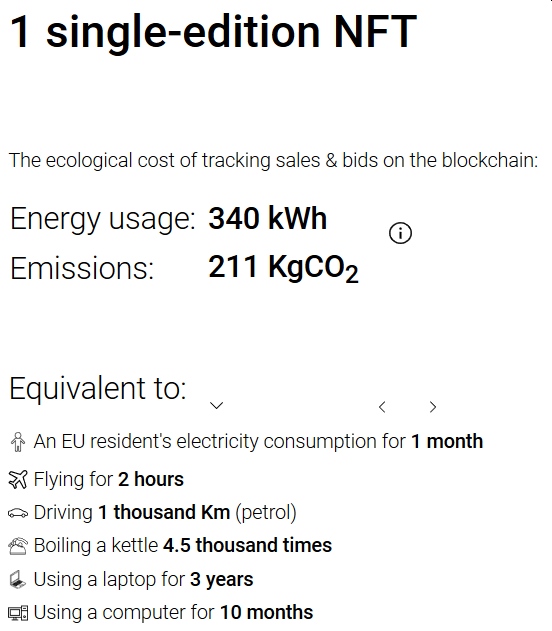

However, the Proof of Work process is also the principal cause of high energy requirements as it is used to validate blockchain transactions, which can include NFT purchases and sales. For example, the energy amount of energy required to create a token (also called “NFT drop”) is 340 kWh. That’s equivalent to the same amount of energy used by an EU resident for about one month or a laptop’s energy consumption over the course of 1.5 years.

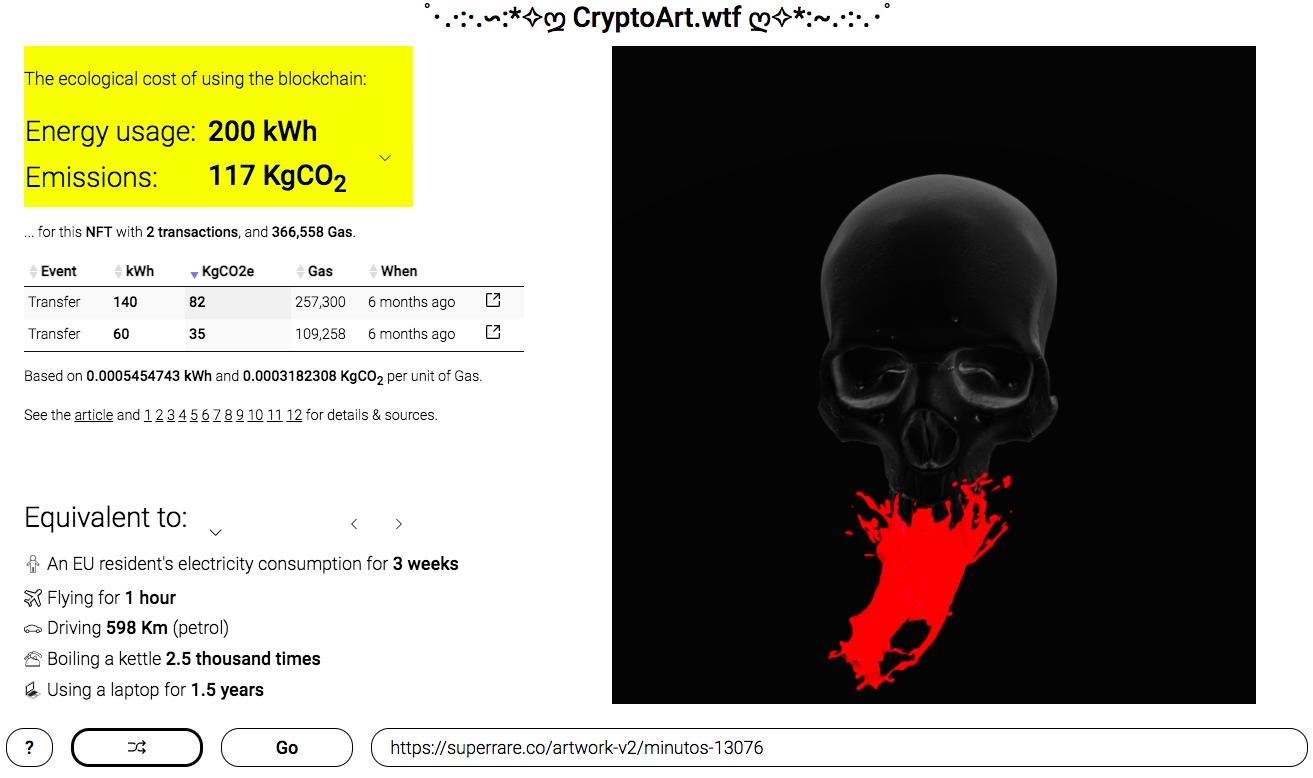

In December 2020, computational artist and engineer Memo Akten launched a website called “CryptoArt.wtf” that calculates the energy usage and CO2 emissions of any NFT on SuperRare, NiftyGateway, or any given URL with an ETH address.

Based on the data collected, Akten found that the average NFT transaction had a bloated footprint of 76kWh, and taking all of the transactions related to a single NFT into account, the average NFT had a footprint of around 340 kWh (or “an EU resident’s total electric power consumption for more than a month”).

This new revelation has caused digital art creator Ten Hundred to abandon his first digital art video after he found out how harmful NFTs are to the environment.

That’s not all. As Akten explained, a single NFT can involve many transactions. These include minting, bidding, canceling, sales, and transfer of ownership. If we were to break down the footprint by transaction type, we get the following

Minting: 142 kWh, 83 KgCO2

Bids: 41 kWh, 24 KgCO2

Cancel Bid: 12 kWh, 7 KgCO2

Sale: 87 kWh, 51 KgCO2

Transfer of ownership: 52 kWh, 30 KgCO2

This generally pushes the footprint of a single NFT into hundreds of kWh, and hundreds of KgCO2 emissions, and often higher. Akten also analyzed about 80000 transactions relating to ~18000 NFTs on the CryptoArt NFT marketplace SuperRare (which is just one of many CryptoArt NFT platforms). Of the ~18000 CryptoArt NFTs that he analyzed, the average NFT has a footprint of around 340 kWh, 211 KgCO2.

To address the energy usage issue, Akten suggests Proof of Stake (PoS) blockchains like ETH2 and Polkadot. Unlike Proof of Work which rewards its miner for solving complex mathematical equations, in Proof of Stake, the individual that creates the next block is based on how much they have ‘staked’. The stake is based on the number of coins the person has for the particular blockchain they are attempting to mine.

Meanwhile, Akten is not alone. In recent years, there have been a number of articles and academic reports citing high electricity usage associated with the Proof of Work validation process used on the Bitcoin and Ethereum networks. Annual greenhouse gas emission estimates from these studies vary, depending on the level of renewable energy used, but can rise into the hundreds of megatons, and are comparable to those of a country like Sweden. However, ethereum.org notes that these validation cycles consume energy at a rate that is largely independent of the level of NFT activity.

In response to these sustainability concerns, the Ethereum Foundation has been moving from “Proof of Work” to a less energy-intensive Proof of Stake type validation protocol, which it predicts will use less than 1% of the energy currently used by the Proof of Work process in Ethereum version 2.0. This transition is expected to be completed by 2022.