Scientists discover new evidence of habitable water ocean under Jupiter’s moon Europa

Europa is the smallest of the four Galilean moons orbiting Jupiter, and the sixth-closest to the planet of all the 79 known moons of Jupiter. It is also the sixth-largest moon in the Solar System. Europa was discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei and was named after Europa, the Phoenician mother of King Minos of Crete and lover of Zeus (the Greek equivalent of the Roman god Jupiter).

Sifting through mined data collected from NASA’s Galileo orbiter launched a generation ago yields new evidence of plumes, eruptions of water vapor, from Jupiter’s moon Europa. Europa is one of the Galilean moons of Jupiter, along with Io, Ganymede, and Callisto. Astronomer Galileo Galilei gets the credit for discovering these moons, among the largest in the solar system. Europa is the smallest of the four but it is one of the more intriguing satellites.

Back in 2018, we wrote about how NASA scientists have discovered the strongest evidence yet for water plumes on Europa. However, NASA’s latest discovery in 2020 slipped under our radar. Fast forward two years later, a new NASA model now supports the theory that the interior ocean in Jupiter’s moon Europa would be able to sustain life. They found that Europa could actually be the best place to look for alien life within our Solar System.

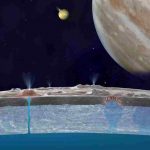

NASA scientists calculated the amount of water they believed to be an ocean under the surface ice shell, which could have been formed by the breakdown of water-containing minerals due to either tidal forces or radioactive decay.

Their work, which was presented for the first time at the 2020 Goldschmidt Conference, is not yet peer-reviewed, but they’re just the latest in a long line of clues that implicate Europa as a possible life-bearing world. The researchers, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, modeled geochemical reservoirs within the interior of Europa using data from the Galileo mission.

“We were able to model the composition and physical properties of the core, silicate layer, and ocean,” said lead researcher Mohit Melwani Daswani. “We find that different minerals lose water and volatiles at different depths and temperatures. We added up this volatiles that are estimated to have been lost from the interior, and found that they are consistent with the current ocean’s predicted mass, meaning that they are probably present in the ocean.”

They found that ocean worlds such as Europa can be formed by metamorphism: in other words, heating and increased pressure caused by early radioactive decay or later subsurface tidal movement, would cause the breakdown of water-containing minerals, and the release of the trapped water.

Then in another paper published in May 2020, a new study, led by ESA research fellow Hans Huybrighs and published in Geophysical Research Letters, scientists discovered new evidence of watery plumes on Jupiter’s moon Europa. Building on previous magnetic field studies by Galileo, scientists explored beneath Europa’s thick blanket of ice for evidence of activity emanating from below.

NASA scientists first discovered the strongest evidence yet for water plumes on Jupiter’s moon Europa in 2018. The initial findings are documented in a paper published in Nature Astronomy, titled: “Evidence of a plume on Europa from Galileo magnetic and plasma wave signatures.” The research was led by Dr. Xianzhe Jia, a space physicist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and the lead author of the journal article. Jia also is co-investigator for two instruments that will travel aboard Europa Clipper, NASA’s upcoming mission to explore the moon’s potential habitability. “The data were there, but we needed sophisticated modeling to make sense of the observation,” Jia said.

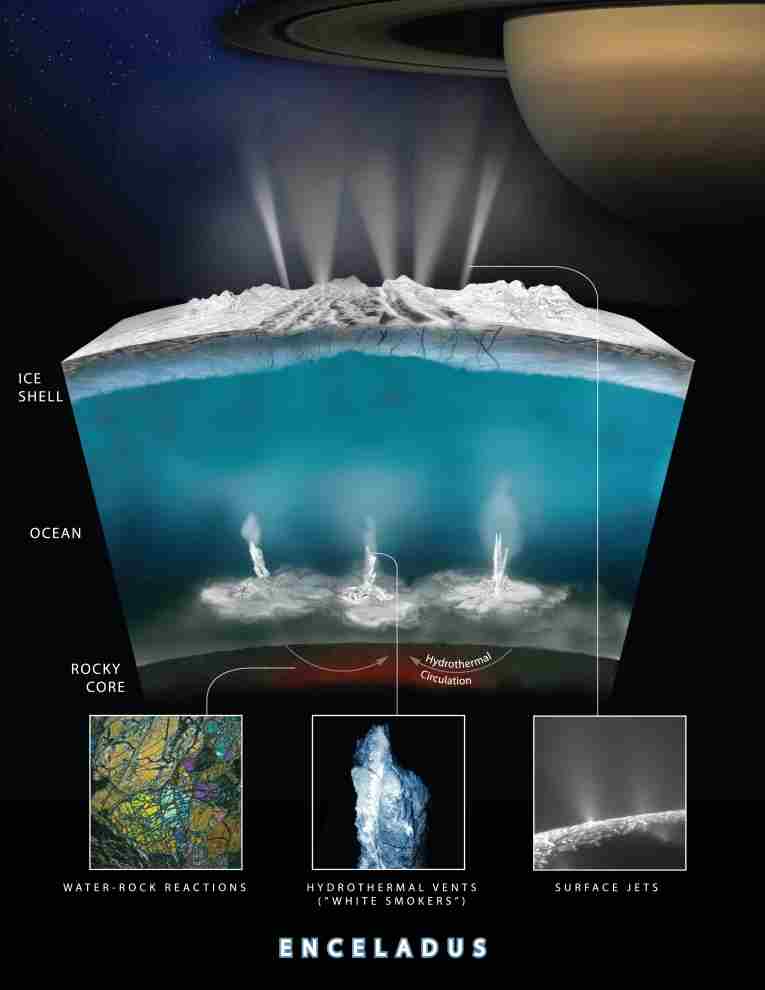

The new findings support earlier insights provided by two veteran NASA missions in April 2017 of new details about icy, ocean-bearing moons of Jupiter and Saturn, further heightening the scientific interest of these and other “ocean worlds” in our solar system and beyond. The findings are presented in papers published by researchers with NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn and Hubble Space Telescope. According to a report from NASA, Cassini scientists announce that a form of chemical energy that life can feed on appears to exist on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, and Hubble researchers report additional evidence of plumes erupting from Jupiter’s moon Europa.

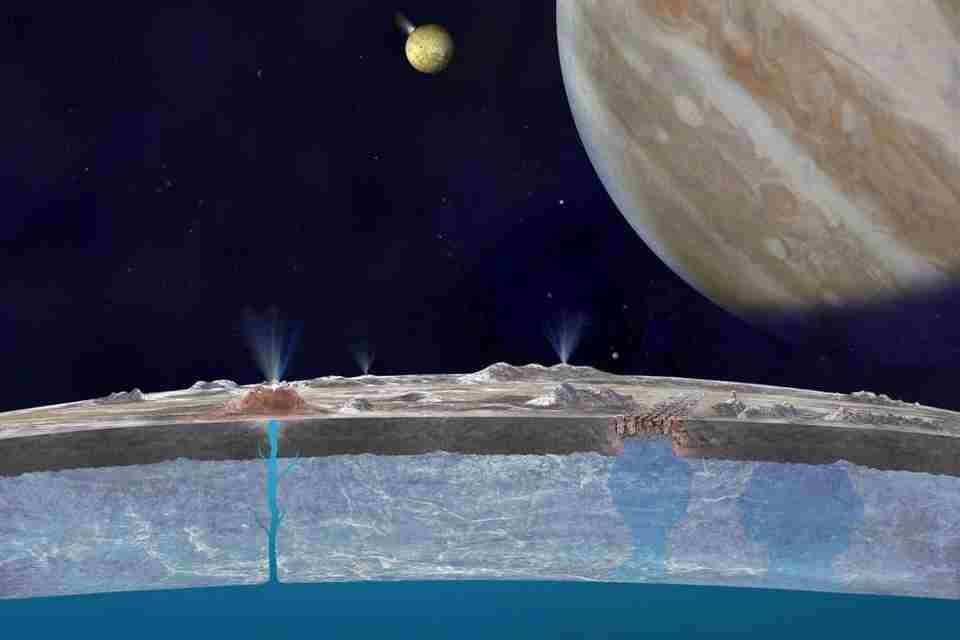

In the earlier report from the new Hubble Space Telescope findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, it provided detailed reports on observations of Europa from 2016 in which a probable plume of material was seen erupting from the moon’s surface at the same location where Hubble saw evidence of a plume in 2014. These images bolster evidence that the Europa plumes could be a real phenomenon, flaring up intermittently in the same region on the moon’s surface. The newly imaged plume rises about 62 miles (100 kilometers) above Europa’s surface, while the one observed in 2014 was estimated to be about 30 miles (50 kilometers) high. Both correspond to the location of an unusually warm region that contains features that appear to be cracks in the moon’s icy crust, seen in the late 1990s by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. Researchers speculate that, like Enceladus, this could be evidence of water erupting from the moon’s interior.

The green oval highlights the plumes Hubble observed on Europa. The area also corresponds to a warm region on Europa’s surface. The map is based on observations by the Galileo spacecraft. Credits: NASA/ESA/STScI/USGS

In the latest research, “data collected by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft in 1997 were put through new and advanced computer models to discover a mystery — a brief, localized bend in the magnetic field — that had gone unexplained until now. Previous ultraviolet images from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope in 2012 suggested the presence of plumes, but this new analysis used data collected much closer to the source and is considered strong, corroborating support for plumes. The findings appear in Monday’s issue of the journal Nature Astronomy,” NASA said.

Jia’s team was inspired to dive back into the Galileo data by Melissa McGrath of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. A member of the Europa Clipper science team, McGrath delivered a presentation to fellow team scientists, highlighting other Hubble observations of Europa.

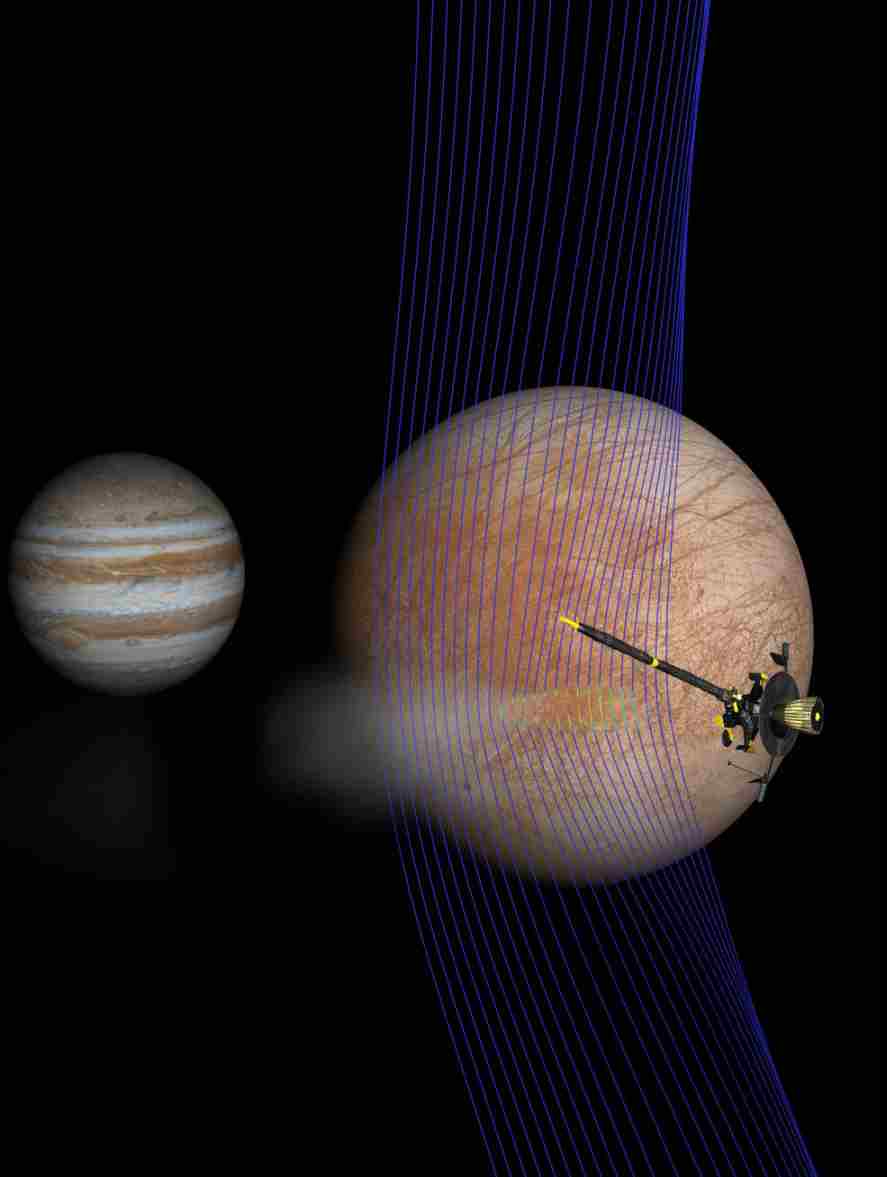

Artist’s illustration of Jupiter and Europa (in the foreground) with the Galileo spacecraft after its pass through a plume erupting from Europa’s surface. A new computer simulation gives us an idea of how the magnetic field interacted with a plume. The magnetic field lines (depicted in blue) show how the plume interacts with the ambient flow of Jovian plasma. The red colors on the lines show more dense areas of plasma. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Michigan

“One of the locations she mentioned rang a bell. Galileo actually did a flyby of that location, and it was the closest one we ever had. We realized we had to go back,” Jia said. “We needed to see whether there was anything in the data that could tell us whether or not there was a plume.”

At the time of the 1997 flyby, about 124 miles (200 kilometers) above Europa’s surface, the Galileo team didn’t suspect the spacecraft might be grazing a plume erupting from the icy moon. Now, Jia and his team believe, its path was fortuitous.

When they examined the information gathered during that flyby 21 years ago, sure enough, high-resolution magnetometer data showed something strange. Drawing on what scientists learned from exploring plumes on Saturn’s moon Enceladus — that material in plumes becomes ionized and leaves a characteristic blip in the magnetic field — they knew what to look for. And there it was on Europa –- a brief, localized bend in the magnetic field that had never been explained.

This graphic illustrates how Cassini scientists think water interacts with rock at the bottom of the ocean of Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, producing hydrogen gas. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Southwest Research Institute

Galileo carried a powerful Plasma Wave Spectrometer (PWS) to measure plasma waves caused by charged particles in gases around Europa’s atmosphere. Jia’s team pulled that data as well, and it also appeared to back the theory of a plume.

But numbers alone couldn’t paint the whole picture. Jia layered the magnetometry and plasma wave signatures into new 3D modeling developed by his team at the University of Michigan, which simulated the interactions of plasma with solar system bodies. The final ingredient was the data from Hubble that suggested dimensions of potential plumes.

The result that emerged, with a simulated plume, was a match to the magnetic field and plasma signatures the team pulled from the Galileo data.

“There now seem to be too many lines of evidence to dismiss plumes at Europa,” said Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “This result makes the plumes seem to be much more real and, for me, is a tipping point. These are no longer uncertain blips on a faraway image.”

The findings are good news for the Europa Clipper mission, which may launch as early as June 2022. From its orbit of Jupiter, Europa Clipper will sail close by the moon in rapid, low-altitude flybys. If plumes are indeed spewing vapor from Europa’s ocean or subsurface lakes, Europa Clipper could sample the frozen liquid and dust particles. The mission team is gearing up now to look at potential orbital paths, and the new research will play into those discussions.

“If plumes exist, and we can directly sample what’s coming from the interior of Europa, then we can more easily get at whether Europa has the ingredients for life,” Pappalardo said. “That’s what the mission is after. That’s the big picture.”

“We show that the location, duration, and variations of the magnetic field and plasma wave measurements are consistent with the interaction of Jupiter’s corotating plasma with Europa if a plume with characteristics inferred from Hubble images were erupting from the region of Europa’s thermal anomalies. These results provide strong independent evidence of the presence of plumes at Europa,” Dr. Xianzhe Jia concluded in a paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy.