New research predicts COVID-19 will become another seasonal bug just like the common cold

After a year in which the coronavirus pandemic changed our ways of life, a big question that is often asked is, how is COVID-19 severity going to change in the years ahead? Now, we may have the answer to this question.

In new research conducted at Emory University and the Department of Biology and Center for Disease Dynamics at Pennsylvania State University, researchers are now predicting that COVID-19 will eventually be “no more virulent than the common cold.” Just like the virus that caused the Spanish flu epidemic in 1918, the team of scientists said COVID-19 will become another seasonal bug that we build efficient long-term immunity against.

The detailed and extensive study, which was published in Science Magazine, provides a positive outlook for the course of the pandemic, especially for young, healthy individuals who have been infected. In the abstract of the study, the researchers said:

“We are currently faced with the question of how the CoV-2 severity may change in the years ahead. Our analysis of immunological and epidemiological data on endemic human coronaviruses (HCoVs) shows that infection-blocking immunity wanes rapidly, but disease-reducing immunity is long-lived. Our model, incorporating these components of immunity, recapitulates both the current severity of CoV-2 and the benign nature of HCoVs, suggesting that once the endemic phase is reached and primary exposure is in childhood, CoV-2 may be no more virulent than the common cold. We predict a different outcome for an emergent coronavirus that causes severe disease in children.”

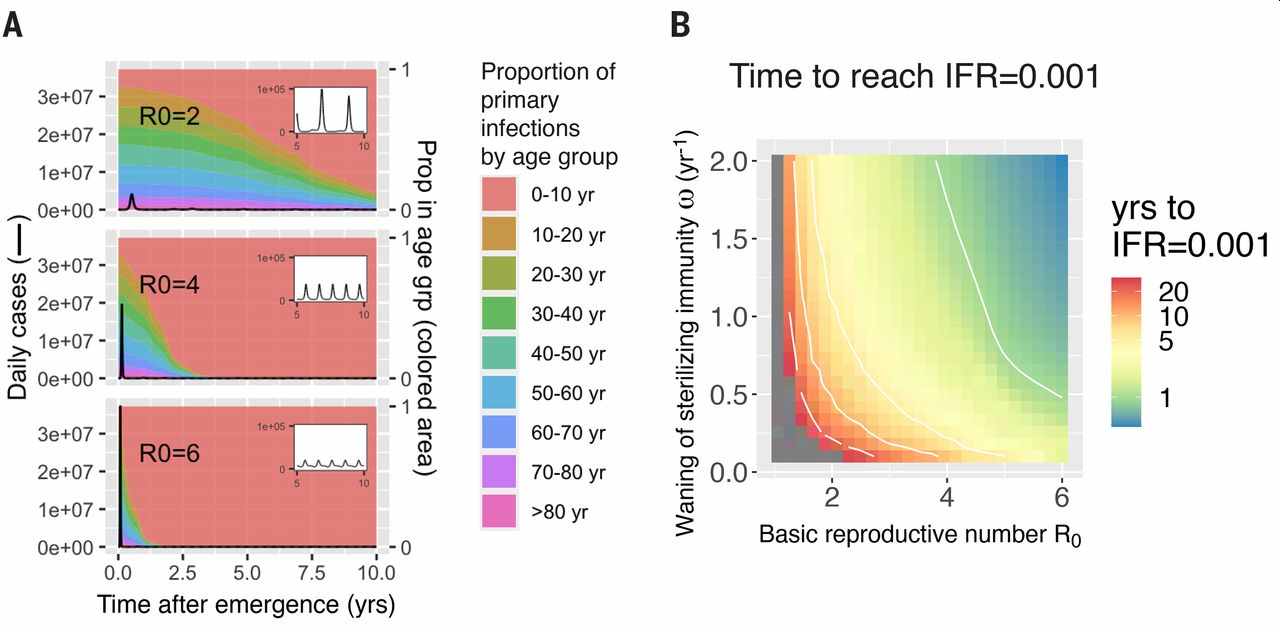

Fig. 2 The time scale of the transition from epidemic to endemic dynamics for emerging coronaviruses depends on R0 and the rate of immune waning. Transition from epidemic to endemic dynamics for emerging HCoVs, simulated from an extension of the model presented in fig. S1 that includes age structure. Demographic characteristics (age distribution, birth, and age-specific death rates) are taken from the United States, and seasonality is incorporated via a sinusoidal forcing function (see SM section 2.2). Weak social distancing is approximated by R0 = 2. (See figs. S9 to S11 for strong social distancing results, R0 < 1.5.) (A) Daily number of new infections (black line, calculations in SM section 2.3). An initial peak is followed by a low-incidence endemic state (years 5 to 10 shown in the inset). A higher R0 results in a larger and faster initial epidemic and more rapid transition to endemic dynamics. The proportion of primary cases in different age groups changes over time (plotted in different colors), and the transition from epidemic to endemic dynamics results in primary cases being restricted to younger age groups. Parameters for simulations: ω = 1 and ρ = 0.7. (B) Time for the average IFR (6-month moving average) to fall to 0.001, the IFR associated with seasonal influenza. Gray areas represent simulations where the IFR did not reach 0.001 within 30 years. The time to IFR = 0.001 decreases as the transmissibility (R0) increases and the duration of sterilizing immunity becomes shorter. Results are shown for ρ = 0.7. See SM section 2.3 and figs. S4 to S7 for sensitivity analyses and model specifications.The study also found that COVID-19 does not cause severe illness in children, unlike other viruses that do. In addition, children, especially those under the age of 10, seem to tolerate the infection, exhibiting only mild symptoms. They also don’t appear to be drivers of disease transmission. The researchers evaluated scenarios for continuing vaccination when the virus falls below pandemic levels because of this pattern. Even for the rollout, they propose:

Should the vaccine cause a major reduction in transmission, it might be important to consider strategies that target delivery to older individuals for whom infection can cause higher morbidity and mortality, while allowing natural immunity and transmission to be maintained in younger individuals.

Wow. That almost sounds like vaccination for the elderly and those at-risk, and herd immunity for younger populations. This analysis has implications for public policy, including challenging the idea that vaccines should be mandatory.

Below is the abstract of the study

“We are currently faced with the question of how the CoV-2 severity may change in the years ahead. Our analysis of immunological and epidemiological data on endemic human coronaviruses (HCoVs) shows that infection-blocking immunity wanes rapidly, but disease-reducing immunity is long-lived. Our model, incorporating these components of immunity, recapitulates both the current severity of CoV-2 and the benign nature of HCoVs, suggesting that once the endemic phase is reached and primary exposure is in childhood, CoV-2 may be no more virulent than the common cold. We predict a different outcome for an emergent coronavirus that causes severe disease in children. These results reinforce the importance of behavioral containment during pandemic vaccine rollout, while prompting us to evaluate scenarios for continuing vaccination in the endemic phase.”