Immune T-cells may offer long-lasting protection against COVID-19. Scientists found some coronavirus patients recovered from COVID-19 infection due to the presence of T-cell immunity

Back in January before the widespread of the coronavirus pandemic, we wrote a piece about how researchers at Cardiff University may have found a cure for cancer after the team of researchers accidentally discovered immune cell (T-cell) that kills most cancers. At the time, the focus was more on how the research could herald a major breakthrough in cancer treatment.

The team of researchers made the discovery when they were analyzing blood from a bank in Wales, looking for immune cells that could fight bacteria, when they found an entirely new type of T-cell. They said the newly-discovered T-cell, which is part of our immune system, could be harnessed to treat all cancers.

Now fast forward eight months later, it seems the same enigmatic T-cell could provide a cure for coronavirus. For months, much of the study on the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has focused on the production of antibodies. However, antibodies are not the only weapons against the coronavirus. Now, researchers are conducting an extensive study on a different type of immune cells known as memory T cells. Unlike the short-term B-cells, The T-cells play an important role in the ability of our immune systems to protect us against many viral infections, including COVID-19.

According to researchers, memory T cells induced by previous pathogens can shape susceptibility to, and the clinical severity of, subsequent infections1. Up until now, little is known about the presence in humans of pre-existing memory T cells that have the potential to recognize severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

In a new study published at medRxiv, scientists discovered that some coronavirus patients who had recovered from infection with Covid-19 mysteriously did not have any antibodies against the novel coronavirus. When they later tested blood samples taken years before the pandemic started, they found the patients have the T-cells that were specifically tailored to detect proteins on the surface of Covid-19. Several other studies have shown that people infected with COVID-19 tend to have T cells that can target the virus, regardless of whether they have experienced symptoms.

So, instead of putting all our eggs in one basket with the production of antibody vaccines that may only offer protection against coronavirus for only six months, we are better served if we invest additional resources in developing vaccines that harness the power of T-cell immunity.

The finding is good news we’ve been waiting for. However, before we pop out the champagne bottle and celebrate, back in April, we also wrote another story about the discovery that coronavirus could also kill the T-cells. According to a study conducted by a team of researchers in China and the US, they found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can destroy the T cells that are supposed to protect the body from the harmful invaders. In their startling discovery, they found that coronavirus can kill immune cells usually used to fight off illness and cause damage similar to what’s seen in HIV patients.

In a new study first published in the journal Nature and led by Antonio Bertoletti and a team of researchers at the Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, they found that these “memory T cells might protect some people newly infected with SARS-CoV-2 by remembering past encounters with other human coronaviruses. This might potentially explain why some people seem to fend off the virus and may be less susceptible to becoming severely ill with COVID-19”

Bertoletti’s team of researchers recognized that many factors could help to explain how a single virus can cause respiratory, circulatory, and other symptoms that vary widely in their nature and severity—as we’ve witnessed in this pandemic. One of those potential factors is prior immunity to other, closely related viruses.

SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, belongs to a large family of coronaviruses, six of which were previously known to infect humans. Four of them are responsible for the common cold. The other two are more dangerous: SARS-CoV-1, the virus responsible for the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which ended in 2004; and MERS-CoV, the virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012.

All six previously known coronaviruses spark the production of both antibodies and memory T cells. In addition, studies of immunity to SARS-CoV-1 have shown that T cells stick around for many years longer than acquired antibodies.

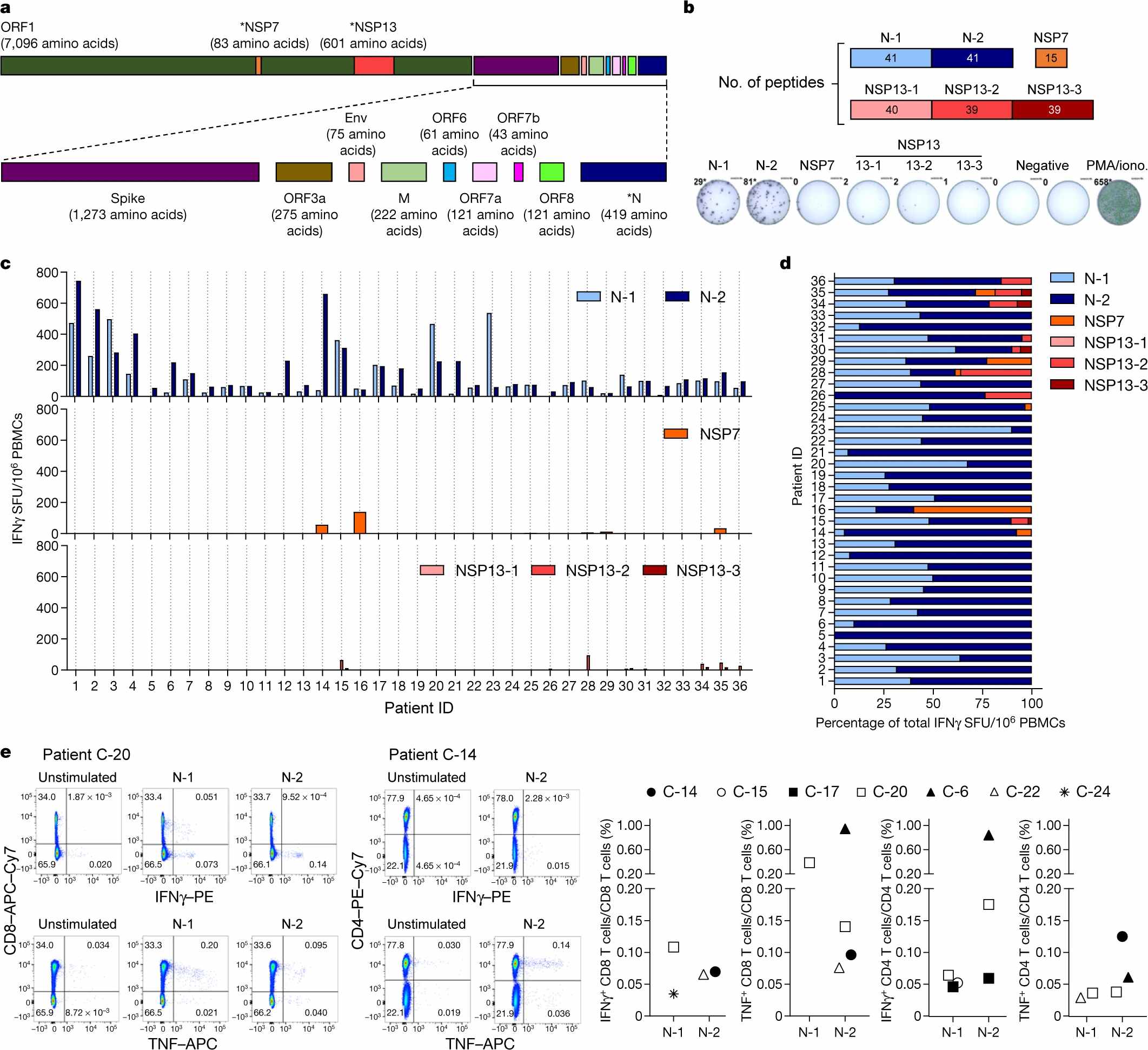

As part of the research, Bertoletti’s team studied T cell responses against the structural (nucleocapsid (N) protein) and non-structural (NSP7 and NSP13 of ORF1) regions of SARS-CoV-2 in individuals convalescing from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (n = 36). In all of these individuals, they found CD4 and CD8 T cells that recognized multiple regions of the N protein.

To study SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associated with viral clearance, Bertoletti’s team collected peripheral blood from 36 individuals after recovery from mild to severe COVID-19 and studied the T cell response against selected structural (N) and non-structural proteins (NSP7 and NSP13 of ORF1) of the large SARS-CoV-2 proteome (Fig. 1a). We selected the N protein as it is one of the more-abundant structural proteins produced and has a high degree of homology between different betacoranaviruses.

a, SARS-CoV-2 proteome organization; analysed proteins are marked by an asterisk. b, The 15-mer peptides, which overlapped by 10 amino acids, comprising the N protein, NSP7 and NSP13 were split into 6 pools covering the N protein (N-1, N-2), NSP7 and NSP13 (NSP13-1, NSP13-2, NSP13-3). c, PBMCs of patients who recovered from COVID-19 (n = 36) were stimulated with the peptide pools or with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (iono) as a positive control. The frequency of spot-forming units (SFU) of IFNγ-secreting cells is shown. d, The composition of the SARS-CoV-2 response in each individual is shown as a percentage of the total detected response. N-1, light blue; N-2, dark blue; NSP7, orange; NSP13-1, light red; NSP13-2, red; NSP13-3, dark red. e, PBMCs were stimulated with the peptide pools covering the N protein (N-1, N-2) for 5 h and analysed by intracellular cytokine staining. Dot plots show examples of patients (2 out of 7) that had CD4 and/or CD8 T cells that produced IFNγ and/or TNF in response to stimulation with N-1 and/or N-2 peptides. The percentage of SARS-CoV-2 N-peptide-reactive CD4 and CD8 T cells in n = 7 individuals are shown (unstimulated controls were subtracted for each response).

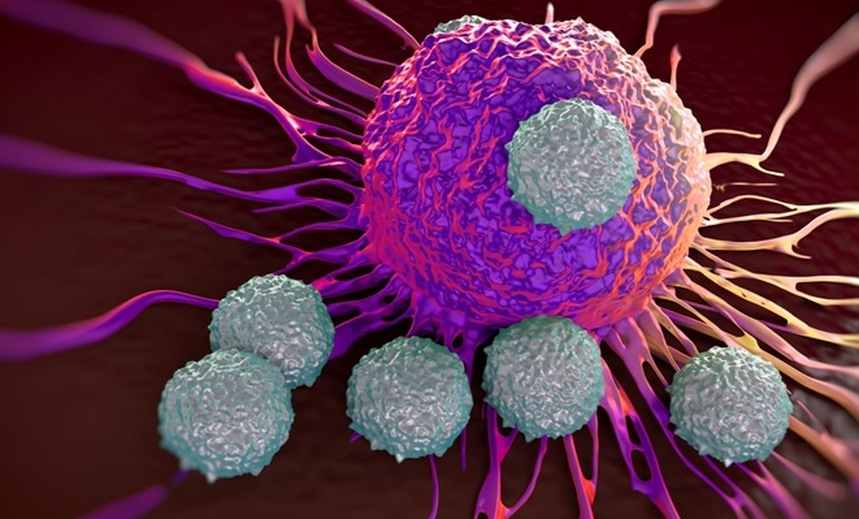

So, what are T-cells? T cells are a kind of immune cell (a type of lymphocyte) whose main purpose is to identify and kill invading pathogens or infected cells. They are a part of the immune system that focuses on specific foreign particles. They do this using proteins on its surface, which can bind to proteins on the surface of these imposters. A T-cell develops in the thymus gland (hence the name) and plays a central role in the immune response. Rather than generically attack any antigens, T-cells circulate until they encounter their specific antigen. As such, T cells play a critical part in immunity to foreign substances.

Most vaccines we use today are based on antibodies but new research has been shown that scientists could harness the power of T-cell as a cure to coronavirus. For example, yesterday we wrote about the Oxford University COVID-19 vaccine that shows positive results in the first phase of human trials; safe and produced an immune response. According to the latest study, the vaccine, called AZD1222 and being developed by AstraZeneca and scientists at Britain’s University of Oxford, did not prompt any serious side effects and elicited antibodies and T-cell immune responses, according to trial results published in The Lancet medical journal.

There are trillions of possible versions of T-cells, each with its own specific function which can each recognize a different target. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell receptor on the cell surface. These immune cells originate as precursor cells, derived from bone marrow, and develop into several distinct types of T-cells once they have migrated to the thymus gland. T cell differentiation continues even after they have left the thymus. Because T-cells can hang around in the blood for years after infection, they also contribute to the immune system’s “long-term memory” and allow it to mount a faster and more effective response when it’s exposed to an old foe.

Below is a quick overview of the T-cell.