Wearing mask outside offers little, if any, protection from coronavirus infection, New England Journal of Medicine study says [Update]

In recent weeks, there’s a nationwide campaign in the United States for everyone to wear masks or face coverings in public places. Even though there’s no conclusive scientific evidence that masks or face coverings provide perfect protection against coronavirus, there are many reports of mask shaming in grocery stores across the country.

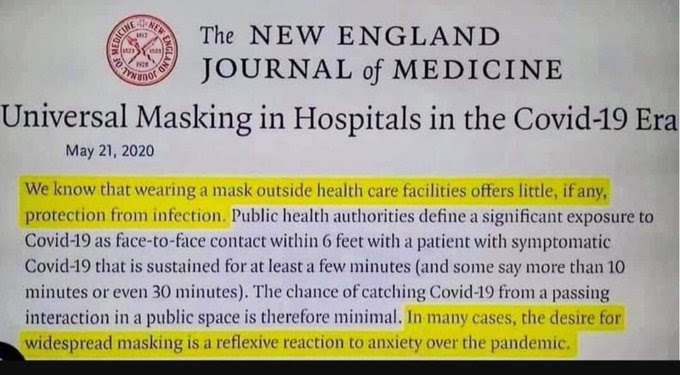

The last known study about the effectiveness mask was published back in May 2020 by the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). In the study, NEJM said, “wearing a mask outside health care facilities offers little, if any, protection from coronanvirus infection.” So, the question is, why are we wearing face mask if it offers little protection from infection?

Many people have cited this study as the reason not to wear masks or facial coverings. Now, NEJM has responded with updated guidance. In an article published on June 3, 2020, NEJM said the following:

“We understand that some people are citing our Perspective article (published on April 1 at NEJM.org)1 as support for discrediting widespread masking. In truth, the intent of our article was to push for more masking, not less. It is apparent that many people with SARS-CoV-2 infection are asymptomatic or presymptomatic yet highly contagious and that these people account for a substantial fraction of all transmissions.2,3 Universal masking helps to prevent such people from spreading virus-laden secretions, whether they recognize that they are infected or not.”

NEJM went on to provide additional clarification:

“We did state in the article that “wearing a mask outside health care facilities offers little, if any, protection from infection,” but as the rest of the paragraph makes clear, we intended this statement to apply to passing encounters in public spaces, not sustained interactions within closed environments. A growing body of research shows that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is strongly correlated with the duration and intensity of contact: the risk of transmission among household members can be as high as 40%, whereas the risk of transmission from less intense and less sustained encounters is below 5%.5-7”

However, in the above quotes, NEJM failed to include the last two lines of the original paragraph which says this: “In many cases, the desire for widespread masking is a reflexive reaction to anxiety over the pandemic.”

The original study published on April 1 at NEJM.org assesses the true value of mask anxiety alleviation. The study suggests that the real reason people wear mask is because wearing masks is a visible reminder of an otherwise invisible yet widely prevalent pathogen and may remind people of the importance of social distancing and other infection-control measures. Below is a screenshot of a section of the study. To avoid any misinformation, below is a screenshot of a section of the study.

The authors of the study found that wearing mask alone will not protect providers caring for a patient with active Covid-19 if it’s not accompanied by meticulous hand hygiene, eye protection, gloves, and a gown.

What is clear, however, is that universal masking alone is not a panacea. A mask will not protect providers caring for a patient with active Covid-19 if it’s not accompanied by meticulous hand hygiene, eye protection, gloves, and a gown.

The article later gave two scenarios in which there may be possible benefits.

The first is during the care of a patient with unrecognized Covid-19. A mask alone in this setting will reduce risk only slightly, however, since it does not provide protection from droplets that may enter the eyes or from fomites on the patient or in the environment that providers may pick up on their hands and carry to their mucous membranes (particularly given the concern that mask wearers may have an increased tendency to touch their faces).

The authors stated that masks still provides some benefits if used within the hospital settings. However, the authors argued that the extent of marginal benefit of universal masking over and above these foundational measures is debatable.

The calculus may be different, however, in health care settings. First and foremost, a mask is a core component of the personal protective equipment (PPE) clinicians need when caring for symptomatic patients with respiratory viral infections, in conjunction with gown, gloves, and eye protection. Masking in this context is already part of routine operations for most hospitals. What is less clear is whether a mask offers any further protection in health care settings in which the wearer has no direct interactions with symptomatic patients.

The study concludes with some symbolic benefits of masks as one of the ways to deal with fear and anxiety, especially during times of crisis. The authors also argued people are better served with data and education than with a marginally beneficial mask, particularly in light of the worldwide mask shortage.

It is also clear that masks serve symbolic roles. Masks are not only tools, they are also talismans that may help increase health care workers’ perceived sense of safety, well-being, and trust in their hospitals. Although such reactions may not be strictly logical, we are all subject to fear and anxiety, especially during times of crisis. One might argue that fear and anxiety are better countered with data and education than with a marginally beneficial mask, particularly in light of the worldwide mask shortage, but it is difficult to get clinicians to hear this message in the heat of the current crisis. Expanded masking protocols’ greatest contribution may be to reduce the transmission of anxiety, over and above whatever role they may play in reducing transmission of Covid-19. The potential value of universal masking in giving health care workers the confidence to absorb and implement the more foundational infection-prevention practices described above may be its greatest contribution.