Coronovirus can live on some surfaces for up to 3 days, scientists test shows

Just three months into the deadly disease, SARS-CoV-2 (also known as 2019-nCoV), the virus that causes COVID-19, has infected more than 120,000 people worldwide and caused more than 4,300 deaths—far more than the 2003 SARS outbreak caused by a genetically similar virus, according to data complied by Johns Hopkins University

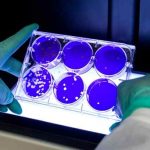

Now in a series of tests conducted by the U.S. government and other scientists, they found that the new coronavirus can live in the air for several hours and on some surfaces for as long as two to three days. Their work was published Wednesday on the medRxiv website, does not prove that anyone has been infected through breathing it from the air or by touching contaminated surfaces, researchers said.

“We’re not by any way saying there is aerosolized transmission of the virus,” but this work shows that the virus stays viable for long periods in those conditions, so it’s theoretically possible, said study leader Neeltje van Doremalen at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

For this study, researchers used a 3-jet Collison nebulizer and fed it into a Goldberg drum to create an aerosolized environment to simulate what might happen if an infected person coughed or made the virus airborne some other way. They found that viable virus could be detected up to three hours later in the air, up to four hours on copper, up to 24 hours on cardboard and up to two to three days on plastic and stainless steel.

Titled “Aerosol and surface stability of HCoV-19 (SARS-CoV-2) compared to SARS-CoV-1,” their test shows that SARS-CoV-2 was most stable on plastic and stainless steel and viable virus could be detected up to 72 hours post application, though by then the virus titer was greatly reduced (polypropylene from 103.7 to 100.6 TCID50/mL after 72 hours, stainless steel from 103.7 to 100.6 104 TCID50/mL after 48 hours, mean across three replicates).

Similar results were obtained from tests they did on the virus that caused the 2003 SARS outbreak, so differences in durability of the viruses do not account for how much more widely the new one has spread, researchers say.

The tests were done at the National Institutes of Health’s Rocky Mountain Lab in Hamilton, Mont., by scientists from the NIH, Princeton University and UCLA, with funding from the U.S. government and the National Science Foundation.