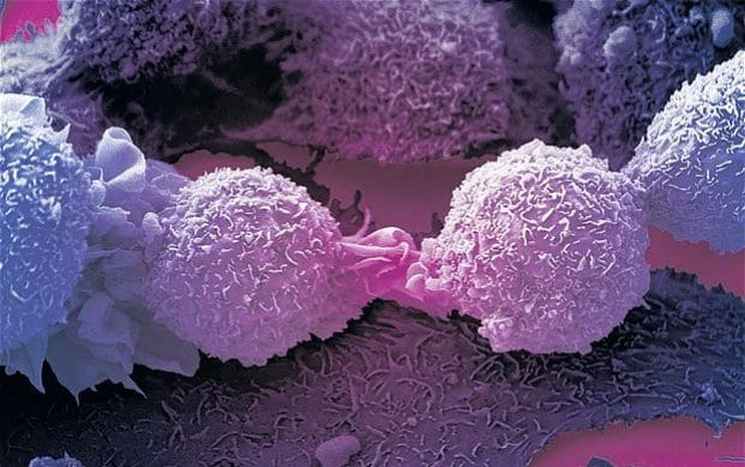

British scientists may have found cure for cancer after accidentally discovered immune cell (T-cell) that kills most cancers

In a finding that could herald a major breakthrough in cancer treatment, British scientists accidentally discovered an immune cell that kills most cancers, according to a report from BBC. The newly discovered T-cells equipped with a new type of T-cell receptor (TCR) recognizes and kills most human cancer types, while ignoring healthy cells. The T-cell recognizes a molecule present on the surface of a wide range of cancer cells, and normal cells, and is able to distinguish between healthy and cancerous cells – killing only the latter.

Researchers at Cardiff University made the discovery when they were analyzing blood from a bank in Wales, looking for immune cells that could fight bacteria, when they found an entirely new type of T-cell. According to the study, this newly-discovered T-cell, which is part of our immune system, could be harnessed to treat all cancers, say scientists.

The new T-cell carries a “never before seen” type of receptor that acts like a grappling hook, latching on to most human cancers. The findings, published in Nature Immunology, have not been tested in patients, but the researchers say they have “enormous potential.” Below is an abstract of the study.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-independent, T cell–mediated targeting of cancer cells would allow immune destruction of malignancies in all individuals. Here, we use genome-wide CRISPR–Cas9 screening to establish that a T cell receptor (TCR) recognized and killed most human cancer types via the monomorphic MHC class I-related protein, MR1, while remaining inert to noncancerous cells. Unlike mucosal-associated invariant T cells, recognition of target cells by the TCR was independent of bacterial loading. Furthermore, concentration-dependent addition of vitamin B-related metabolite ligands of MR1 reduced TCR recognition of cancer cells, suggesting that recognition occurred via sensing of the cancer metabolome. An MR1-restricted T cell clone mediated in vivo regression of leukemia and conferred enhanced survival of NSG mice. TCR transfer to T cells of patients enabled killing of autologous and nonautologous melanoma. These findings offer opportunities for HLA-independent, pan-cancer, pan-population immunotherapies.

Experts said that although the work was still at an early stage, it was very exciting. However, in multiple laboratory studies, immune cells equipped with the new receptor were shown to kill lung, skin, blood, colon, breast, bone, prostate, ovarian, kidney and cervical cancer.

Professor Andrew Sewell, the lead author on the study from Cardiff University’s School of Medicine, said it was “highly unusual” to find a TCR with such broad cancer specificity and this raised the prospect of “universal” cancer therapy.

Professor Sewell added: “We hope this new TCR may provide us with a different route to target and destroy a wide range of cancers in all individuals. Current TCR-based therapies can only be used in a minority of patients with a minority of cancers. ”

“Cancer-targeting via MR1-restricted T-cells is an exciting new frontier – it raises the prospect of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ cancer treatment; a single type of T-cell that could be capable of destroying many different types of cancers across the population.”

Professor Andrew Sewell, from Cardiff University’s School of Medicine, where the discovery of a new type of killer immune cell has raised the prospect of a ‘universal’ cancer therapy. Photograph: PA.