MIT Study: AI Could Replace 11.7% of U.S. Jobs and Put $1.2 Trillion in Wages at Risk

Artificial intelligence has long been framed as a future disruption. A new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) argues the future is already here. According to MIT, existing AI systems are capable of replacing or directly impacting 11.7% of the U.S. labor market, putting as much as $1.2 trillion in wages at risk across finance, healthcare, professional services, logistics, human resources, and office administration.

The findings are powered by a simulation system called the Iceberg Index, built by MIT in partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Instead of relying on broad economic forecasts or sector-level estimates, the index models how 151 million workers across the United States interact, move, and perform tasks, then measures how much of that work today’s AI can already handle. The result is a detailed, skills-first view of exposure that shows where disruption is quietly building, far beyond the visible wave of tech layoffs making headlines.

“AI is transforming work. We have spent years making AIs smart—they can read, write, compose songs, shop for us. But what happens when they interact? When millions of smart AIs work together, intelligence emerges not from individual agents but from the protocols that coordinate them. Project Iceberg explores this new frontier: how AI agents coordinate with each other and humans at scale,” MIT wrote.

MIT’s “Iceberg Index” and The True Scale of AI’s Impact on American Workers

The Iceberg Index, announced earlier this year, is a large-scale simulation built by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), a Department of Energy research center in eastern Tennessee and home to the Frontier supercomputer, which powers many large-scale modeling efforts. It models what MIT refers to as an “Agentic US” — a synthetic population of more than 151 million humans interacting with thousands of AI agents inside a shared economic environment.

Running on systems at ORNL, the platform acts as a sandbox where researchers study how humans and AI systems coordinate on tasks, how new automation capabilities ripple through thousands of individual skills, and how those shifts affect specific communities across the country.

“Basically, we are creating a digital twin for the U.S. labor market,” said Prasanna Balaprakash, ORNL director and co-leader of the research, according to CNBC.

Instead of treating work as job titles, the model breaks tasks down and links them to more than 32,000 skills mapped across 923 occupations and over 3,000 counties. Each simulated worker is represented as an individual agent, assigned a location, skill set, and occupation. That level of detail allows the system to map where current AI systems already overlap with human work — and where pressure may build next.

The goal is not to deliver predictions about exact hiring numbers or job-loss timelines. Iceberg offers a skills-based snapshot of what AI can already do and what that means for workers, communities, and training programs long before those changes show up in official employment data.

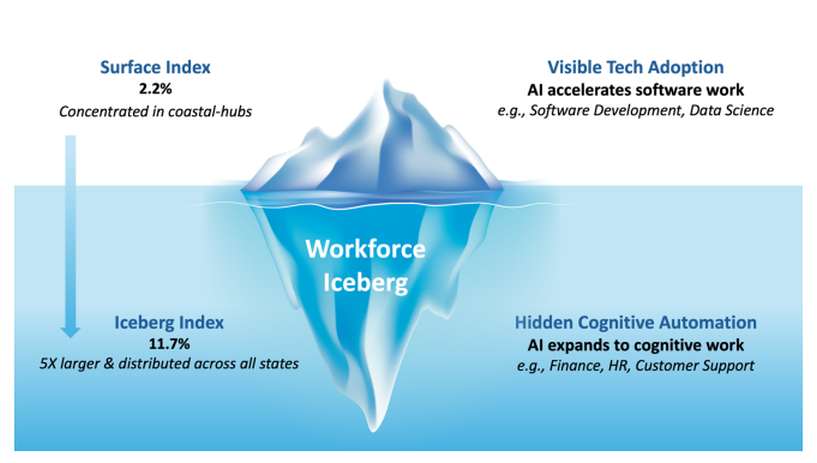

Credit: MIT

What most people see today in tech layoffs and role shifts represents only a small fraction of the broader exposure. According to the model, the visible layer accounts for just 2.2% of total wage risk, or about $211 billion. Beneath the surface sit the rest of the routine functions in fields like HR, finance, logistics, and office support that are already well within AI’s reach. These often-overlooked areas make up the bulk of the $1.2 trillion figure.

The research team frames Iceberg as a tool for planning rather than prediction. It allows governments and institutions to test ideas in a controlled environment before committing large-scale investments in reskilling, workforce development, and infrastructure.

That practical focus has already drawn in state-level partners. Tennessee, North Carolina, and Utah collaborated with MIT and ORNL to validate the model using their own labor data. Tennessee moved first, incorporating Iceberg’s insights into its official AI Workforce Action Plan released this month. Utah is preparing a similar report guided by the platform’s findings.

North Carolina state Sen. DeAndrea Salvador, who has worked closely with MIT on the project, said what stood out was the model’s ability to reveal impacts traditional tools miss.

“One of the things that you can go down to is county-specific data to essentially say, within a certain census block, here are the skills that is currently happening now and then matching those skills with what are the likelihood of them being automated or augmented, and what could that mean in terms of the shifts in the state’s GDP in that area, but also in employment,” she said.

That level of detail is proving valuable as states form AI task forces, pilot programs, and layered strategies. Iceberg provides them with a shared, data-backed foundation.

The simulations are already challenging a common assumption — that AI-related job disruption will stay mostly in coastal, tech-heavy regions. The data shows exposure across all 50 states, including inland and rural areas often excluded from the conversation. According to Iceberg, AI’s reach is a nationwide shift, not a geographic exception.

The research team has also built an interactive environment that lets policymakers explore different paths forward. They can test the effects of shifting workforce funds, altering training priorities, or adjusting the pace of AI adoption in specific sectors, all before allocating significant public money.

“Project Iceberg enables policymakers and business leaders to identify exposure hotspots, prioritize training and infrastructure investments, and test interventions before committing billions to implementation,” the report says.

Balaprakash, who also sits on the Tennessee Artificial Intelligence Advisory Council, has shared localized insights with the governor’s office and the state’s AI director. He noted that several of Tennessee’s core sectors — including health care, nuclear energy, manufacturing, and transportation — still rely heavily on physical labor, offering some insulation from purely digital automation. The bigger question ahead is how AI systems and robotics can be used to reinforce those industries rather than hollow them out.

For now, the team behind Iceberg sees the project as an evolving sandbox. A place to run new scenarios, experiment with outcomes, and prepare for shifts that are already underway.

“It is really aimed towards getting in and starting to try out different scenarios,” Salvador said.